Why private equity investors are turning to the rental sector

21 September 2021

Private equity investors are buying more equipment rental businesses in 2021 than ever before. Lucy Barnard asks what sort of deals PE investors are looking for in the sector and why.

Out in the red dust of the Pilbara region in Western Australia, a housing block which was once part of the athletes’ village in the Sydney Olympics is one of 3,400 remote accommodation rooms and 259,000 modular units to quietly change hands as part of a private equity deal signed in Toronto and London.

A metal plaque on the side of a housing block in the remote Roy Hill mining village, announces that the room was originally supplied by Ausco, part of vast modular accommodation specialist Modulaire, to house the world’s top athletes.

Modulaire’s model of renting portable accommodation blocks which can be quickly set up, used as anything from classrooms for schools to offices in building sites, and easily taken away and re-purposed, made the company the subject of one of the most high-profile takeover deals in the sector this year as private equity firms around the world swooped on the plant hire sector.

Brookfield Business Partners, a listed unit of Canadian investment firm Brookfield Asset Management, which eventually beat rival Onex Corp and went on to lead a $5bn acquisition of Modulaire (owner of Algeco) from London-based TDR Capital in June, said that it had decided to splash the cash for two main reasons: It expected the equipment rental business to benefit from government stimulus measures in construction sectors around the world in the wake of the pandemic; and short term economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic would result in a wave of company decisions to lease temporary space for their workers rather than committing to new offices.

“The business is well positioned to benefit from industry tailwinds including growing infrastructure and public sector investment, said Anuj Ranjan, managing partner at Brookfield Business Partners. “And where there is increased demand for leasing or modular solutions to replace permanent construction.”

And Brookfield was far from the only PE investor with an eye on the growth prospects for the modular space sector.

What is private equity?Private equity firms are organisations which specialize in buying up businesses which are struggling or have potential and repackaging them to speed up growth. They often operate by raising big debts to acquire their targets and to invest in them. Companies can range in size from fairly small players to conglomerates like the Blackstone Group or the Carlyle Group which can spend billions of dollars on buying up businesses, even against the will of company boards. Typically private equity firms are not listed on public exchanges and manage funds which either invest directly into private companies or engage in company buyouts which result in de-listing businesses and taking them private. Most PE firms are owned by their founders, managers or a limited group of investors. These firms usually invest money on behalf of institutional investors such as pension funds, sovereign governments or extremely wealthy individuals. They promise to use this money to grow companies over a 4-5 year investment period making healthy returns in the process. Private equity firms court controversy because they tend to buy up businesses using Leveraged Buy Outs (LBOs) where they buy companies by loading them up with debt. PE firms promise to use this extra capital to invest in companies, helping them grow. However, critics accuse them of asset stripping and focusing on generating quick returns rather than long term investment. |

In May West Street Global Infrastructure Partners IV, a private equity investment firm managed by Goldman Sachs Asset Management, closed a SEK8.1bn (€798m) deal to take temporary accommodation rental company, Adapteo, which operates in Sweden, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands.

Goldman Sachs Infrastructure Investment Partners

“We have reviewed the social infrastructure and modular space rental sectors extensively and are excited by Adapteo’s strong infrastructure characteristics,” said Phillippe Camu, global co-head and co-chief investment officer of Goldman Sachs’ infrastructure investment group.

Elsewhere in the equipment rental sector, more deals were being done by PE players. These included One Equity Partners’ $73m acquisition of the North American arm of the AMECO heavy equipment and tools rental business from engineering and construction firm Fluor Corp.

And TDR Capital, the private equity company which sold Modulaire to Brookfield, was also acquiring in the sector. Alongside infrastructure investment manager I Squared Capital, TDR led a £2.32bn take-private deal for Aggreko, the world leader in power and temperature control rentals and large temporary power projects.

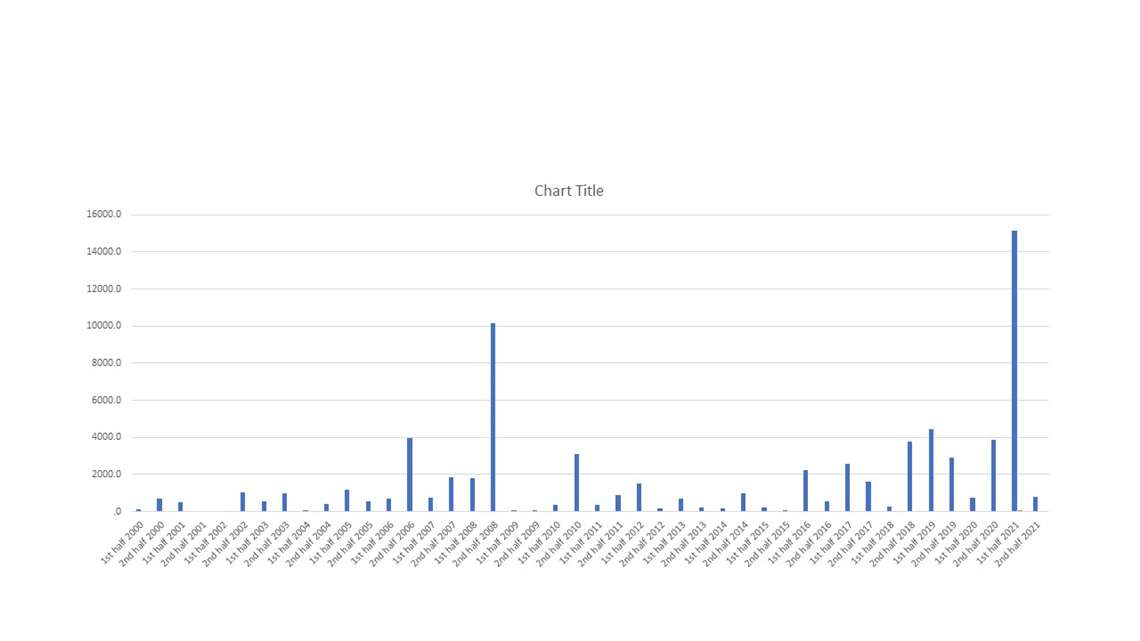

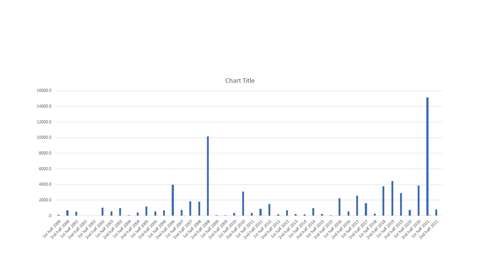

According to figures from financial data specialist Refinitiv, in total, private equity investors contributed to a record US$15.1bn in 55 deals buying construction equipment and rental companies in the first six months of 2021, the highest amount ever recorded since records began 20 years ago (see graph). And so far, Refinitiv calculates that there have been another 23 deals in the second half of the year, worth another $778.1m.

The figure is more than three times the total amount invested by private equity firms in the whole of 2020 when PE backed M&A volumes in the rental sector stood at US$4.6bn. And it also dwarfs the $7.3bn figure for 2019 before buying activity had been affected by the pandemic.

PE-backed M&A volumes involving targets in the construction equipment and rental sector. Source: Refinitiv

PE-backed M&A volumes involving targets in the construction equipment and rental sector. Source: Refinitiv

“Without doubt we are seeing more interest from PE in the equipment rental space this year than ever before,” says Jeff Eisenberg, CEO at Claremont Consulting, a firm advising PE investors about buying in the sector. “The level of activity in 2021 has been way beyond our expectations at the start of the year.”

He points out that the flurry of acquisitions mirrors a wider market trend of PE megadeals fuelled by cheap debt and last year’s pause in deal making activity caused by the global pandemic.

Refinitiv calculates that in the first half of 2021 alone, PE groups spent a total of $513bn on businesses around the world with some of the highest profile deals including CDP, Blackstone and Macquarie Group’s $9.7bn deal to acquire Italian toll road business ASPI, and Madison Capital Partners’ $3.6bn deal to acquire the Nortek Air Management business of turbine manufacturer Melrose.

And it seems likely that there is still more to come.

North America reserves of $976bn

Financial data company Prequin estimated that in September 2020, North American private equity firms alone were sitting on reserves of $976bn – their highest on record - as investors continued to plough money into PE funds in the expectation of high returns.

“There is a lot of dry powder in Europe and the US searching for good investments,” Eisenberg says. “The pandemic stopped some deals going through last year so there is a lot of pent-up demand. And at the same time there is a lot of cheap debt because interest rates are low and central banks are printing money. All of that creates a lot of appetite and a lot of desire to buy those assets.”

Picture courtsey of Marco Verch Professional Photographer via Flickr

Picture courtsey of Marco Verch Professional Photographer via Flickr

Nayim Khemais, a principal at NBK Capital Partners, a subsidiary of the National Bank of Kuwait which manages a number of private equity and private debt funds, adds that with construction firms around the world under pressure to cut their carbon footprints, PE firms are looking for ways to use their investment to exploit any sustainability angles they can find.

“Investors at the moment have a thesis to move to renewable energy and hybrid solutions,” he says. “A new PE investor will come in with a good growth story for investment targets where they can invest in ‘greener’ equipment.”

Khemais, who actively manages generator rental specialist Energia in Saudi Arabia through a mezzanine loan, points out that private equity investors have been investing in construction equipment rental firms for many years, attracted by the sector’s asset-backed profile which can provide investment security.

The figures seem to stack up. Khemais says that an energy rental company in KSA can rent out a 1 MW generator for around $10,000 a month in Saudi Arabia compared to much lower in US and Europe where they can fetch around $5,000 a month. The cost to buy a similar generator would be around $250,000, although equipment hire firms must also cover additional costs such as maintenance and delivery.

By putting money into equipment rental outfits, PE fund managers hope that they can gain exposure to the potentially high returns of the infrastructure-related industries without the risks associated with acquiring a developer or contractor. And, to some extent the market can be counter-cyclical, with contractors more likely to rent equipment rather than buy if they are expecting a downturn.

Aggreko is one of the equipment rental businesses recently acquired by private equity.

Aggreko is one of the equipment rental businesses recently acquired by private equity.

“This is a sector that has a quite interesting return profile,” Khemais says. “It has a short payback period and a high return on invested capital because when you buy the equipment you can turn it many times,” he says.

“Equipment rental is quite defensive because cashflows can be controlled in a downturn,” he adds. “If the market slumps, you can basically turn off the capex and not buy more equipment. And, if you need to recoup losses, your fleet usually has a good residual value. You can sell equipment on the secondary market or you can put them up for auction. It gives you a certain cushion which in itself also makes the sector quite attractive from a risk perspective.”

And, it’s not just “traditional” PE firms who are on the prowl for acquisitions at the moment, fund managers report increased competition from “family offices,” privately held firms that handle investment management for wealthy families or people with over $100m under management, which can have just as much firepower as private equity funds and are more flexible and far less bound by the need to provide returns to investors within a 4-5 year timeframe.

Covid cash pile up

“We see a lot of competition now coming from non-traditional sources of capital such as family offices and strategic players who have been piling up cash and sitting on it due to Covid,” Khemais says. “They come in with a longer time frame – with buy and hold strategies. At the same time they can be more flexible when it comes to valuation and structuring the deal and even the size of the deals. They can buy cheaper, smaller ticket assets or pay higher multiples given longer holding horizons. And sometimes they can structure in more creative ways. And that creates more competition in the PE world and is pushing a lot of PE firms to think about holding assets for a longer time.”

Picture courtesy of Fsecart via Flickr

Picture courtesy of Fsecart via Flickr

With a seemingly ever-increasing flock of PE players chasing a limited number of large equipment hire companies, Eisenberg predicts that investors must be willing to pay top dollar.

Fund managers typically value companies by establishing a price tag based on how much money is coming in and out of the business. Historically, PE firms would try to pay under or around six times EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) for equipment rental businesses.

However, these days, with PE firms competing against each other for targets, that multiple is rising fast. In the modular building space, Adapteo’s SEK8.1bn valuation represents a multiple of nine times the company’s 2020 earnings. Brookfield paid around 12 times Modulaire’s (Algeco’s) 2020 EBITDA.

“We are definitely expecting more PE-backed deals to take place in the equipment rental space over the coming months but I think there has to be some concern that assets are becoming over-valued,” Eisenberg says. “We have already seen EBITDA multiples rise to historic highs and it seems likely that a combination of cheap debt and optimism about growth will push company values even higher.”

TDR’s strategy for ModulaireFor London-based TDR, investment in Modulaire appears to have proved lucrative. TDR bought a 66.98% stake in Modulaire, then known as Algeco, in 2004 for €320m from German tourism company TUI. TDR then went on to grow the company through a string of acquisitions before selling 70% of the company’s North American modular leasing business Williams Scotsman for $1.1bn to Double Eagle Acquisition Group in 2017 and its North American remote accommodation business Target Lodging for $820m to Platinum Eagle Acquisition Corp in 2019 before offloading the remainder to Brookfield this year for $5bn. “The investment thesis behind our original acquisition was the inherent value dislocation between leasing earnings and sales earnings,” TDR said in a statement. “During TDR’s ownership, we have repositioned the business away from manufacturing and sales towards a more sustainable and profitable rental model.” |

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM