Is the impending death of the diesel combustion engine exaggerated?

17 March 2023

Whether it is the rush towards on-road electric vehicles or the steady stream of announcements from OEMs about their latest electric construction machinery, it can feel like the days of the diesel combustion engine are numbered.

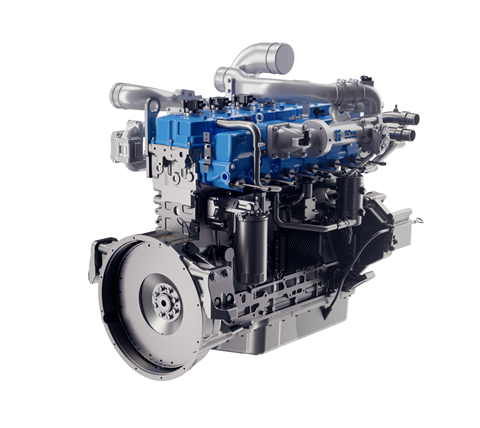

Hyundai Doosan Infracore will launch a new 11 L hydrogen engine at ConExpo. (Photo: Hyundai Doosan Infracore)

Hyundai Doosan Infracore will launch a new 11 L hydrogen engine at ConExpo. (Photo: Hyundai Doosan Infracore)

In fact, while the range of electrically powered construction machines has increased drastically over the past few years, they still account for only a very small proportion of global sales. In Europe, it is perhaps 0.5% - almost all in small machine classes like mini excavators and compact wheel loaders.

In China, the number of electric vehicles sold is slightly higher thanks to the supply of larger wheel loaders and excavators up to about 20t.

But Off-Highway Research estimates the share of sales taken up by electric machines in China is still at most 1%.

Diesel-powered machines still dominate the off-highway landscape.

In the context of the Paris Agreement to reduce global warming to 1.5°C, that’s a problem.

But the death of the combustion engine, if not diesel itself, may have been exaggerated.

“OEMs are becoming jaded about the internal combustion engine (ICE), especially in the light vehicles area, and I think that is a mistake,” Dr Allen Aradi, fuels scientist at Shell Global Solutions, told the Diesel Progress Summit last year.

“It may not look feasible and convenient right now but as you approach 2050, you will find that low-carbon fuels and the combustion systems that burn them will become very important”.

Limitations of battery electric and fuel cells

Full electric machines will of course be part of the mix. But they won’t suit every application in construction, particularly at the heavier end of the scale. Batteries involve particular challenges when it comes to humidity and thermal management. That mean that combustion engines are often still preferable in certain harsh operating environments.

The new hydrogen refueller between JCB’s hydrogen powered telehandler and backhoe loader. (Photo: JCB)

The new hydrogen refueller between JCB’s hydrogen powered telehandler and backhoe loader. (Photo: JCB)

And then there is the cost. Anecdotally, an electric version of a compact tracked loader, for example, can currently end up more than double the price of its diesel-powered equivalent. Whereas a consumer may be prepared to pay extra to make a statement about their stance on the environment, for contractors around the world, it’s most likely to be the bottom line that determines buying decisions.

Charging machines could also prove to be a challenge, particularly in remote locations or where the time required to replenish the battery could interfere with scheduled work.

Energy from “green” hydrogen fuel cells also have the potential to be part of the solution but aren’t likely to be able to satisfy the energy and power intensity of all construction and earthmoving equipment. Some argue that fuel cells are also susceptible to harsh conditions, including humidity, altitude, dust, and shock and vibration. But companies developing them claim that durability is improving, with a fuel cell unit paired with a battery able to run as long or longer than a diesel engine. Where fuel cells are less advantageous is their high cost and the fact that the hydrogen required to run them still relatively difficult to obtain.

One of the principal advantages of diesel powertrains is that they are very compact. The drivetrain and energy storage take up less space than either a fuel cell system with no battery, which requires far more space for energy storage, or electric battery, which requires less space for the drivetrain but again far more for the energy storage. And when the energy storage volume on a machine cannot be increased, then its operating time until refuelling has to decrease.

Combustion engines here to stay – but need to change

Diesel engines are already 95% cleaner than they were in terms of emissions. They have also become more efficient but not to the extent that they can solve the carbon emissions challenge. Construction will need to wean itself off diesel in order to hit its carbon reduction targets.

Cummins is to display 15l fuel-agnostic engines at ConExpo 2023

Cummins is to display 15l fuel-agnostic engines at ConExpo 2023

But that’s not to say that combustion engines can’t remain part of the mix, alongside battery electric and fuel cells. “Virtually all engine manufacturers are looking at electrification and fuel cells.

“But combustion engines will be around for a long time in my opinion, especially off-road, where electrification is challenged to address the needs of the applications,” says Mike Brezonick, vice president of editorial at KHL Group’s power division.

Dr Ingo Wintruff, managing director of Liebherr’s combustion engine business, speaking at last year’s Diesel Progress Summit, said, “The concern is not the combustion engine but the fuel that is burned. Combustion engines have unbeatable advantages under harsh conditions and they have become favourable for higher energy and higher power densities.”

What’s more, the injection technology for alternative fuels, particularly hydrogen, already exists. While accepting that combustion is not the one and only solution, Liebherr is working to develop a high parts commonality among its ICEs to allow for minimal adaption of its engines in order to allow them to handle different fuels.

Fuel availability for “zero” ICEs presents challenges

That’s not to say that alternative fuels for combustion engines are without challenges.

ICEs running on hydrotreated vegetable oils (HVO) are already relatively commonplace in certain regions. In late 2022, for example, construction and infrastructure contractor BAM committed to HVO fuels as part of the strategy for the decarbonisation of its operations by 2026.

Not everyone agrees on the approach, however. In a position paper released last year, Balfour Beatty pointed to “serious issues” with HVO in terms of its traceability and carbon footprint claims which it said needed to be “ironed out” before it could commit.

The disagreement points to a wider uncertainty around not just the claims around the sustainability of alternative fuels but also their ability to keep up with potential demand.

JCB unveiled its first zero-carbon emissions hydrogen-fuelled engine at ConExpo 2023 in Last Vegas, US. The company has invested £100 million (US$120 million) in the project and already has working prototypes running in a backhoe loader and telescopic handler. It has also developed a mobile refuelling system, which allows hydrogen to be taken from onsite tube trailers and distributed to machines by a refueller as they work on the job site, in a similar way to using a bowser to refuel diesel machines.

Nonetheless, one industry insider described the infrastructure to refuel hydrogen-powered engines as “pre-natal”. Unsurprising, considering that the engine technology itself is still in the early stages.

John Deere’s JD14 and JD18 are currently capable of burning hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) and biodiesel up to B20 as a direct diesel replacement. (Photo: Diesel Progress staff)

John Deere’s JD14 and JD18 are currently capable of burning hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) and biodiesel up to B20 as a direct diesel replacement. (Photo: Diesel Progress staff)

If alternative fuels like HVO or hydrogen for combustion engines are to help in the construction industry’s efforts to decarbonise, then they will require very rapid scaling up, in addition to cast-iron assurances about their sustainability.

Dr Aradi, while presenting to the Diesel Progress Summit, noted, “On the fuel side, we need to do a lot more basic science so we can pass that on to OEMs so they can properly optimise their engines.” He said that such fuels are a “must” rather than a choice and that they have the potential to offset demand for diesel. But the volumes at which they are produced are not going to keep up with demand unless something happens.

While there is enough availability of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), hydrotreated vegetable oils (HVO), ethanol and methanal to satisfy demand until 2035, Aradi indicated that more scaling up would be required to meet demand from 2035-2050.

In the case of more exotic options like bio naphtha, bio natural gas, hydrogen (blue of green) and ammonia, there isn’t currently enough availability and they would require even further scaling up to meet future demand.

He called for a road map and collaboration between fuel suppliers, OEMs and regulators to establish production process and ramp up volumes.

Aradi said he saw the need to implement “nature-based solutions” to grow feed stocks and stressed that they will need to be sustainable. And he suggested fixing water management problems in semi-arid, low-populations areas like equatorial Africa, before turning land there to biomass growth.

He added, “And then when we come to regulators, they need to simplify the process for introducing these new molecules into the market. Fuel suppliers and OEMs need to put pressure on the regulators to make sure that as these zero-carbon fuels become feasible and available, we run them right into the market without the usual red tape.”

Diesel to predominate for now

Work to make diesel “cleaner”, particularly as far as particulate and NOx emissions are concerned, is likely to continue.

The EU’s Stage V non-road emissions standards for non-road vehicles are currently the most stringent in the world.

Meanwhile, the US is likely to move towards Tier 5 standards, with implementation likely around 2026-27.

And China implemented the first China National Standard 4 off-road regulations last year, covering all diesel non-road equipment under 560kW. The standards are based on EU Stage 3B, with the addition of limits on particle counts that result in the requirement to use a diesel particulate filter. The standard for smaller engines (under 37kW) is modelled after Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Tier 2 standards.

A continued focus on reducing the harmful emissions from diesel engines reflects the fact that are likely to predominate in off-highway construction applications for some time to come.

Predicting the future, particularly in light of the events of the last few years, has become something of a mug’s game.

But it is likely to take decades before other forms of power generation start to overtake diesel engines.

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM